David Albert Review of a Universe From Nothing

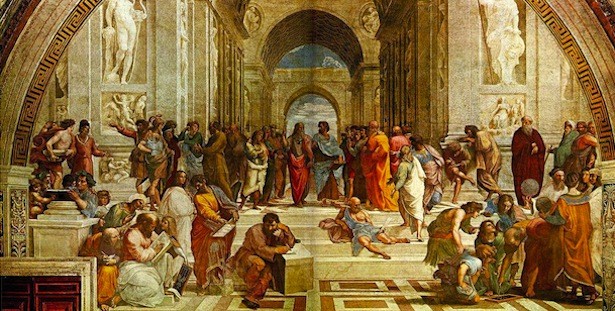

It is hard to know how our hereafter descendants will regard the piffling sliver of history that we live in. It is difficult to know what events volition seem of import to them, what the narrative of now volition expect similar to the 25th-century mind. We tend to remember of our time as ane uniquely shaped by the accelerate of technology, just more and more than I suspect that this will be remembered every bit an age of cosmology—equally the moment when the homo mind first internalized the cosmos that gave rise to it.

Over the by century, since the discovery that our universe is expanding, science has quietly begun to sketch the construction of the entire creation, extending its explanatory powers across a hundred billion galaxies, to the dawn of infinite and time itself. It is breathtaking to consider how quickly nosotros have come to understand the basics of everything from star formation to galaxy formation to universe germination. And now, equipped with the predictive power of quantum physics, theoretical physicists are get-go to push fifty-fifty farther, into new universes and new physics, into controversies one time thought to be squarely inside the domain of theology or philosophy.

In January, Lawrence Krauss, a theoretical physicist and Director of the Origins Institute at Arizona State University, published A Universe From Naught: Why There Is Something Rather Than Nothing, a book that, as its title suggests, purports to explain how something—and not just any something, but the entire universe—could have emerged from nix, the kind of zip implicated past breakthrough field theory. But before attempting to do so, the book beginning tells the story of modernistic cosmology, whipping its manner through the large bang to microwave background radiations and the discovery of night energy.

It's a story that Krauss is well positioned to tell; in recent years he has emerged equally an unusually gifted explainer of astrophysics. I of his lectures has been viewed over a meg times on YouTube and his cultural reach extends to some unlikely places—last twelvemonth Miley Cyrus came under fire when she tweeted a quote from Krauss that some Christians found offensive. Krauss's volume quickly became a bestseller, drawing raves from pop atheists like Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins, the latter of which even compared it to The Origin of Species for the fashion its terminal chapters were supposed to finally upend the "last trump card of the theologian."

By early leap, media coverage of A Universe From Nothing seemed to have run its grade, but then on March 23, The New York Times ran a blistering review of the book, written by David Albert, a philosopher of physics from Columbia University. Albert, who has a Ph.D. in theoretical physics, argued that Krauss'southward "nothing" was in fact a something and did and then in uncompromising terms:

"The particular, eternally persisting, elementary physical stuff of the globe, according to the standard presentations of relativistic quantum field theories, consists (unsurprisingly) of relativistic quantum fields... they have nothing whatsoever to say on the subject area of where those fields came from, or of why the world should take consisted of the particular kinds of fields it does, or of why it should have consisted of fields at all, or of why at that place should accept been a world in the first identify. Period. Case closed. Stop of story."

Because the story of modern cosmology has such deep implications for the fashion that we humans meet ourselves and the universe, it must be told correctly and without exaggeration—in the classroom, in the printing and in works of popular science. To see two academics, both versed in theoretical physics, disagreeing and so intensely on such a cardinal point is troubling. Not considering scientists shouldn't disagree with each other, merely because hither they're disagreeing about a merits beingness disseminated to the public every bit a legitimate scientific discovery. Readers of popular science often assume that what they're reading is backed by a strong consensus. Having recently interviewed Krauss for a different project, I reached out to him to see if he was interested in discussing Albert's criticisms with me. He said that he was, and mentioned that he would be traveling to New York on April 20 to speak at a memorial service for Christopher Hitchens. As information technology happened, I was besides due to be in New York that weekend and then, terminal Fri, we were able to sit down downwardly for the extensive, and at times contentious, chat that follows.

Ross Andersen: I know that yous're just coming from Christopher Hitchens' memorial service. How did that go?

Lawrence Krauss: It was a remarkable issue for a remarkable homo, and I felt very fortunate to be at that place. I was invited to give the opening presentation in front of all of these literary figures and dignitaries of various sorts, and then I began the only way I remember you can brainstorm, and that's with music from Monty Python. That got me over my initial stage fearfulness and my business organisation nearly what to say about someone as extraordinary equally Christopher. I was able to talk about a lot of the aspects of Christopher that people may non know about, including the fact that he was fascinated by science. And I also got to talk about what it felt like to be his friend.

I closed with an anecdote, a true story virtually the last time I was with him. I was reading The New York Times at his kitchen table, and there was an article nearly the ongoing effort to continue Cosmic students at elite colleges like Yale from losing their religion. The article said something like "faced with Nietzsche, coed dorms, Hitchens, and beer pong, students are probable to stray." There are two really astonishing aspects of that. For one, to be then culturally ubiquitous that you tin be mentioned in a sentence like that without any farther explanation is pretty exceptional. Simply also to exist sandwiched between "Nietzsche" and "beer pong" is an honor that very few of us can ever aspire to.

Andersen: I desire to start with a full general question virtually the relationship between philosophy and physics. There has been a fair corporeality of sniping betwixt these 2 disciplines over the past few years. Why the sudden, public animosity between philosophy and physics?

Krauss: That'south a skillful question. I expect information technology's because physics has encroached on philosophy. Philosophy used to be a field that had content, but and then "natural philosophy" became physics, and physics has simply continued to make inroads. Every fourth dimension in that location'due south a jump in physics, it encroaches on these areas that philosophers accept advisedly sequestered abroad to themselves, and and so so you have this natural resentment on the function of philosophers. This sense that somehow physicists, because they tin't spell the discussion "philosophy," aren't justified in talking about these things, or oasis't thought deeply virtually them—

Andersen: Is that really a claim that you see ofttimes?

Krauss: Information technology is. Philosophy is a field that, unfortunately, reminds me of that old Woody Allen joke, "those that tin't exercise, teach, and those that can't teach, teach gym." And the worst part of philosophy is the philosophy of science; the only people, as far as I tin tell, that read work past philosophers of scientific discipline are other philosophers of scientific discipline. It has no touch on physics what so ever, and I doubt that other philosophers read it considering it'south fairly technical. Then information technology's really difficult to understand what justifies it. And so I'd say that this tension occurs because people in philosophy feel threatened, and they have every right to feel threatened, because science progresses and philosophy doesn't.

Andersen: On that note, y'all were recently quoted as maxim that philosophy "hasn't progressed in two thousand years." Just informatics, peculiarly research into artificial intelligence was to a large degree congenital on foundational piece of work done by philosophers in logic and other formal languages. And certainly philosophers like John Rawls accept been immensely influential in fields similar political science and public policy. Do y'all view those as legitimate achievements?

Krauss: Well, yes, I mean, look I was being provocative, as I tend to do every now and then in order to get people's attention. There are areas of philosophy that are of import, only I think of them every bit beingness subsumed by other fields. In the case of descriptive philosophy y'all have literature or logic, which in my view is really mathematics. Formal logic is mathematics, and there are philosophers like Wittgenstein that are very mathematical, but what they're really doing is mathematics—it's not talking nearly things that have affected informatics, it's mathematical logic. And again, I think of the interesting work in philosophy as beingness subsumed past other disciplines like history, literature, and to some extent political scientific discipline insofar as ethics can be said to fall under that heading. To me what philosophy does all-time is reflect on knowledge that's generated in other areas.

Andersen: I'm not certain that'southward correct. I think that in some cases philosophy actually generates new fields. Computer science is a perfect example. Certainly philosophical work in logic tin can be said to have been subsumed by informatics, but subsumed might be the wrong word—

Krauss: Well, you proper name me the philosophers that did cardinal work for computer science; I remember of John Von Neumann and other mathematicians, and—

Andersen: But Bertrand Russell paved the mode for Von Neumann.

Krauss: Only Bertrand Russell was a mathematician. I mean, he was a philosopher too and he was interested in the philosophical foundations of mathematics, but by the fashion, when he wrote about the philosophical foundations of mathematics, what did he exercise? He got it wrong.

Andersen: But Einstein got it wrong, too—

Krauss: Sure, but the difference is that scientists are really happy when they get information technology incorrect, because it means that in that location's more to learn. And look, ane can play semantic games, but I call back that if you await at the people whose work really pushed the computer revolution from Turing to Von Neumann and, yous're correct, Bertrand Russell in some general manner, I think yous'll find it's the mathematicians who had the big impact. And logic can certainly be claimed to exist a part of philosophy, just to me the content of logic is mathematical.

Andersen: Practise you find this same tension betwixt theoretical and empirical physics?

Krauss: Sometimes, but it shouldn't be in that location. Physics is an empirical scientific discipline. Every bit a theoretical physicist I can tell you that I recognize that it's the experiment that drives the field, and information technology's very rare to have it go the other fashion; Einstein is of grade the obvious exception, but even he was guided by observation. It'due south ordinarily the universe that's surprising u.s., non the other mode around.

Andersen: Moving on to your book A Universe From Nothing, what did you lot hope to accomplish when y'all prepare out to write information technology?

Krauss: Every time I write a book, I attempt and think of a hook. People are interested in science, but they don't ever know they're interested in science, then I try to notice a way to go them interested. Teaching and writing, to me, is really merely seduction; yous become to where people are and you find something that they're interested in and y'all endeavour and apply that to convince them that they should exist interested in what y'all have to say.

The religious question "why is there something rather than naught," has been around since people have been around, and now we're actually reaching a point where science is start to address that question. And then I figured I could utilize that question as a way to celebrate the revolutionary changes that we've achieved in refining our movie of the universe. I didn't write the book to assail organized religion, per se. The purpose of the book is to bespeak out all of these amazing things that nosotros now know virtually the universe. Reading some of the reactions to the volume, it seems like you automatically get strident the minute you effort to explain something naturally.

Richard Dawkins wrote the afterword for the book—and I idea it was pretentious at the time, but I just decided to go with it—where he compares the volume to The Origin of Species. And of course as a scientific piece of work information technology doesn't some close to The Origin of Species, which is 1 of the greatest scientific works always produced. And I say that as a physicist; I've oft argued that Darwin was a greater scientist than Einstein. But in that location is one similarity betwixt my book and Darwin's—earlier Darwin life was a miracle; every attribute of life was a miracle, every species was designed, etc. And so what Darwin showed was that uncomplicated laws could, in principle, plausibly explain the incredible diversity of life. And while we don't withal know the ultimate origin of life, for about people it's plausible that at some point chemistry became biology. What'due south astonishing to me is that we're now at a bespeak where we can plausibly argue that a universe total of stuff came from a very uncomplicated starting time, the simplest of all beginnings: nada. That's been driven by profound revolutions in our agreement of the universe, and that seemed to me to exist something worth celebrating, and so what I wanted to do was use this question to become people to face up this remarkable universe that we live in.

Andersen: Your book argues that physics has definitively demonstrated how something can come from nil. Do you mean that physics has explained how particles can sally from so-called empty space, or are yous making a deeper claim?

Krauss: I'm making a deeper claim, just at the same time I think yous're overstating what I argued. I don't think I argued that physics has definitively shown how something could come up from aught; physics has shown how plausible physical mechanisms might cause this to happen. I attempt to exist intellectually honest in everything that I write, especially near what we know and what nosotros don't know. If you're writing for the public, the i thing you can't exercise is overstate your claim, because people are going to believe yous. They see I'grand a physicist and then if I say that protons are niggling pink elephants, people might believe me. And so I effort to be very careful and responsible. We don't know how something can come from nothing, but we do know some plausible means that it might.

But I am certainly claiming a lot more than than just that. That information technology's possible to create particles from no particles is remarkable—that you can exercise that with impunity, without violating the conservation of energy and all that, is a remarkable thing. The fact that "nil," namely empty infinite, is unstable is amazing. Merely I'll be the beginning to say that empty space as I'yard describing it isn't necessarily nothing, although I volition add that it was enough practiced enough for Augustine and the people who wrote the Bible. For them an eternal empty void was the definition of nothing, and certainly I show that that kind of nothing ain't nothing anymore.

Andersen: But debating physics with Augustine might not exist an interesting thing to practise in 2012.

Krauss: It might exist more interesting than debating some of the moronic philosophers that have written about my book. Given what we know about quantum gravity, or what nosotros presume about quantum gravity, we know you can create infinite from where there was no space. And and so you've got a situation where there were no particles in infinite, only also at that place was no space. That'south a lot closer to "nothing."

But of course then people say that's non "goose egg," because you can create something from it. They inquire, justifiably, where the laws come from. And the last office of the volume argues that nosotros've been driven to this notion—a notion that I don't like—that the laws of physics themselves could exist an environmental accident. On that theory, physics itself becomes an ecology scientific discipline, and the laws of physics come into being when the universe comes into existence. And to me that's the concluding nail in the bury for "nothingness."

Andersen: It sounds like you lot're arguing that 'nothing' is really a quantum vacuum, and that a quantum vacuum is unstable in such a way as to make the production of matter and space inevitable. But a quantum vacuum has properties. For one, it is bailiwick to the equations of quantum field theory. Why should nosotros think of it as nothing?

Krauss: That would be a legitimate argument if that were all I was arguing. By the manner it'due south a nebulous term to say that something is a quantum vacuum in this mode. That'south another term that these theologians and philosophers have started using considering they don't know what the hell it is, merely it makes them sound like they know what they're talking well-nigh. When I talk about empty space, I am talking about a quantum vacuum, but when I'm talking almost no space whatsoever, I don't meet how you can telephone call information technology a quantum vacuum. Information technology'southward truthful that I'thousand applying the laws of quantum mechanics to it, but I'k applying it to nothing, to literally zero. No infinite, no time, nothing. There may have been meta-laws that created it, only how yous tin phone call that universe that didn't exist "something" is beyond me. When you lot go to the level of creating space, you take to argue that if there was no space and no time, there wasn't any pre-existing quantum vacuum. That's a later phase.

Even if you have this argument that nothing is non cypher, you have to acknowledge that nada is being used in a philosophical sense. But I don't really requite a damn virtually what "nothing" means to philosophers; I intendance about the "cipher" of reality. And if the "zero" of reality is full of stuff, then I'll get with that.

But I don't have to accept that argument, because space didn't exist in the country I'm talking about, and of course then yous'll say that the laws of quantum mechanics existed, and that those are something. But I don't know what laws existed so. In fact, most of the laws of nature didn't be before the universe was created; they were created along with the universe, at least in the multiverse picture. The forces of nature, the definition of particles—all these things come up into beingness with the universe, and in a dissimilar universe, different forces and dissimilar particles might exist. Nosotros don't nonetheless have the mathematics to describe a multiverse, and and then I don't know what laws are fixed. I also don't have a quantum theory of gravity, so I can't tell you for sure how space comes into beingness, but to make the argument that a quantum vacuum that has particles is the same every bit ane that doesn't take particles is to non understand field theory.

Andersen: I'chiliad not sure that anyone is arguing that they're the same thing—

Krauss: Well, I read a moronic philosopher who did a review of my book in the New York Times who somehow said that having particles and no particles is the same affair, and it's non. The quantum country of the universe can change and it's dynamical. He didn't empathize that when yous apply quantum field theory to a dynamic universe, things change and you lot can go from one kind of vacuum to another. When you go from no particles to particles, information technology means something.

Andersen: I think the problem for me, coming at this as a layperson, is that when you're talking about the explanatory power of science, for every stage where you have a "something,"—fifty-fifty if it'southward just a wisp of something, or even merely a ready of laws—in that location has to be a further question almost the origins of that "something." Then when I read the title of your volume, I read it as "questions about origins are over."

Krauss: Well, if that claw gets yous into the volume that's slap-up. But in all seriousness, I never brand that claim. In fact, in the preface I tried to exist actually clear that you can keep asking "Why?" forever. At some level there might be ultimate questions that we can't answer, but if we tin can answer the "How?" questions, we should, because those are the questions that affair. And it may but be an infinite set of questions, but what I point out at the end of the volume is that the multiverse may resolve all of those questions. From Aristotle's prime number mover to the Catholic Church'due south get-go cause, we're always driven to the thought of something eternal. If the multiverse really exists, then you could have an infinite object—infinite in time and infinite as opposed to our universe, which is finite. That may beg the question as to where the multiverse came from, only if it's infinite, it's infinite. You might not be able to answer that terminal question, and I try to be honest about that in the book. But if you can show how a ready of physical mechanisms can bring about our universe, that itself is an amazing affair and it's worth jubilant. I don't e'er claim to resolve that infinite regress of why-why-why-why-why; equally far as I'm concerned it's turtles all the mode down. The multiverse could explain it by existence eternal, in the same way that God explains it past being eternal, only there's a huge deviation: the multiverse is well motivated and God is but an invention of lazy minds.

Andersen: In the past you've spoken quite eloquently nearly the Multiverse, this idea that our universe might be ane of many universes, perhaps an infinite number. In your view does theoretical physics give a convincing business relationship of how such a construction could come to be?

Krauss: In certain means, yes—in other ways, no. There are a variety of multiverses that people in physics talk about. The most convincing 1 derives from something called aggrandizement, which we're pretty certain happened because information technology produces effects that agree with almost everything we can find. From what we know virtually particle physics, it seems quite likely that the universe underwent a period of exponential expansion early. But aggrandizement, insofar equally we understand it, never ends—it merely ends in certain regions and and so those regions become a universe like ours. You can show that in an inflationary universe, y'all produce a multiverse, you produce an infinite number of causally separated universes over fourth dimension, and the laws of physics are different in each ane. There'southward a real mechanism where you lot can calculate it.

And all of that comes, theoretically, from a very small region of space that becomes infinitely big over time. There's a calculable multiverse; it's virtually required for aggrandizement—it'due south very hard to get around it. All the evidence suggests that our universe resulted from a period of inflation, and it's strongly suggestive that well across our horizon there are other universes that are beingness created out of inflation, and that most of the multiverse is still expanding exponentially.

/media/img/posts/2018/10/multiverse/original.png)

Andersen: Is there an empirical borderland for this? How do we discover a multiverse?

Krauss: Correct. How do you tell that there'due south a multiverse if the residue of the universes are outside your causal horizon? It sounds like philosophy. At all-time. But imagine that we had a fundamental particle theory that explained why in that location are three generations of cardinal particles, and why the proton is two 1000 times heavier than the electron, and why there are four forces of nature, etc. And it also predicted a flow of inflation in the early universe, and information technology predicts everything that we come across and yous can follow information technology through the unabridged evolution of the early universe to see how we got here. Such a theory might, in add-on to predicting everything we see, also predict a host of universes that we don't see. If we had such a theory, the accurate predictions it makes well-nigh what we tin see would also brand its predictions about what nosotros can't run across extremely likely. And then I could run across empirical evidence internal to this universe validating the beingness of a multiverse, even if we could never run into it directly.

Andersen: You have said that your volume is meant to describe "the remarkable revolutions that have taken place in our understanding of the universe over the past 50 years—revolutions that should be celebrated every bit the height of our intellectual feel." I think that'due south a worthy project and, like you, I find it sad that some of physics' well-nigh extraordinary discoveries have yet to fully penetrate our culture. Only might it be possible to communicate the beauty of those discoveries without tacking on an assault on previous conventionalities systems, peculiarly when those belief systems aren't necessarily scientific?

Krauss: Well, yes. I'm sympathetic to your point in 1 sense, and I've had this debate with Richard Dawkins; I've often said to him that if you want people to mind to you, the best way is not to go up to them and say, "You're stupid." Somehow it doesn't become through.

It's a fine line and it's hard to tell where to fall on this one. What drove me to write this volume was this discovery that the nature of "zero" had changed, that we've discovered that "nothing" is nigh everything and that it has backdrop. That to me is an amazing discovery. So how practise I frame that? I frame information technology in terms of this question about something coming from nothing. And role of that is a reaction to these really pompous theologians who say, "out of null, nothing comes," because those are just empty words. I think at some signal y'all need to provoke people. Science is meant to make people uncomfortable. And whether I went too far on ane side or another of that line is an interesting question, simply I suspect that if I can become people to be upset nigh that event, and so on some level I've raised awareness of it.

The unfortunate aspect of information technology is, and I've come up to realize this recently, is that some people feel they don't even need to read the book, because they think I've missed the point of the fundamental theological question. Simply I doubtable that those people weren't open to information technology anyway. I think Steven Weinberg said it all-time when he said that science doesn't get in incommunicable to believe in God, it only makes it possible to not believe in God. That'due south a profoundly of import point, and to the extent that cosmology is bringing us to a identify where we can address those very questions, it's undoubtedly going to brand people uncomfortable. It was a judgment phone call on my function and I tin't go back on it, so it's hard to know.

Andersen: You've developed this wonderful ability to translate difficult scientific concepts into linguistic communication that tin enlighten, and even inspire a layperson. There are people in organized religion communities who are genuinely curious well-nigh physics and cosmology, and your book might be merely the thing to quench and multiply that curiosity. But I worry that by framing these discoveries in language that is in some sense borrowed from the culture state of war, that you run the risk of shrinking the potential audition for them—and that could ultimately be a disservice to the ideas.

Krauss: Ultimately, it might be. I've gone to these fundamentalist colleges and I've gone to Fox News and information technology's interesting, the biggest touch on I've always had is when I said, "you don't take to be an atheist to believe in evolution." I've had young kids come up to me and say that affected them deeply. So yeah it's nice to signal that out, but I actually think that if y'all read my volume I never say that we know all the answers, I say that it's pompous to say that we can't know the answers. And and then yeah I call back that possibly in that location will be some people who are craving this stuff and who won't pick up my book because of the manner I've framed it, but at the same time I practice recollect that people need to exist aware that they tin be dauntless plenty to ask the question "Is it possible to understand the universe without God?" So yous're right that I'one thousand going to lose some people, simply I'grand hoping that at the same time I'll gain some people who are going to be brave enough to come out of the cupboard and ask that question. And that'due south what amazes me, that present when you lot merely ask the question you're told that you're offending people.

Andersen: But let me bring that back full circle. You opened this conversation talking about seduction. You're not giving an account of seduction right at present.

Krauss: That'due south true, simply let me take information technology back full circle to Hitchens. What Christopher had was charm, humor, wit and civilization as weapons against nonsense, and in my ain small fashion what I endeavour and do in my books is exactly that. I try and infuse them with humor and civilisation and that's the seduction part. And in this case the seduction might exist causing people to inquire, "How can he say that? How can he have the temerity to suggest that it'due south possible to get something from nothing? Let me see what's wrong with these arguments." If I'd just titled the book "A Marvelous Universe," not equally many people would have been attracted to it. Just it'south hard to know. I'm acutely aware of this seduction problem, and my hope is that what I can do is go people to listen long enough to where I can show some of what's going on, and at the same time make them laugh.

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2012/04/has-physics-made-philosophy-and-religion-obsolete/256203/

0 Response to "David Albert Review of a Universe From Nothing"

Enregistrer un commentaire